I’ve been waiting for Still Writing for a long time, ever since Dani first mentioned her new project to our class, sitting in her living room, surrounded by books. Oh, those books! Those books, alphabetized by author’s name and categorized by type, over which my eyes glided so many times during the hours I was immensely privileged to sit in Dani’s house as a member of her writing class. I learned more than I can possibly articulate from Dani and from my classmates during the 2 1/2 years I participated. I left Dani’s workshop this past winter during a time in my life when I felt simultaneously overwhelmed by responsibilities and demands and painfully aware of how short my childrens’ time at home was. I miss it, but I will never forget what I learned, and I know I’ll be enriched for the rest of my writing days by my time in the class.

All of this preamble is to say: I’m wildly fortunate to be able to call Dani my teacher. Reading Still Writing felt like listening to Dani talk, and I can tell you first-hand that that’s an immense gift. Still Writing is full of both specific ideas for and wise observations about the writing life, and it contains the kind of language that makes my eyes fill with tears and the kind of richness that I think about for days, weeks, and months.

At the outset of Still Writing, Dani asserts that “the page is your mirror” and quotes Emerson on how the good writer “seems to be writing about himself, but has his eye always on that thread of the universe which runs through himself and all things.” These two images together remind us that every day a writer deals with the granular reality of him or herself and also with the largest questions of human experience. Still Writing does the exact same thing. Dani tells stories from her own life, both to show us how she came to be the writer she is and to demonstrate certain truths about the creative life. She also makes concrete suggestions which are pragmatic and thought-provoking in equal measure. Still Writing is studded with quotes from other writers and thinkers; by weaving these words with her own Dani both adds resonance to her narrative and affirms her place in the highest choir of those who write about writing.

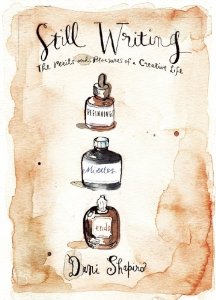

The book is structured in three parts: Beginnings, Middles, and Endings.

Beginnings are about facing down our internal censor, about finding a place to sit that is a room of one’s own, and of locating the “shimmer around the edges” that Joan Didion described. To begin is to find what Dani describes as a toehold – whether that’s character or place or dialogue or plot – and to release our need for permission. To write is to sit down, over and over again, to stay with something when it gets hard, not to look away. “The practice is the art,” Dani reminds us. There is no avoiding doing the work. At the beginning it is also particularly useful to have a guide, and when Dani describes her first mentor, Grace Paley (to whom Still Writing is dedicated), I found myself nodding vigorously. As I read Dani say of Paley, “I often found myself on the verge of tears when I was in her presence,” I was myself in tears. The fact is that’s precisely how I felt about Dani when I first met her, and how I continue to feel. There are people who touch something deep inside us, in whom we recognize something kindred and also something to which we aspire. Dani is one of those people for me.

Middles are about courage and quiet tenacity, about muses and finding the right early readers, about identifying the subconscious tics that fill our work and the inheritance and history that colors and shapes our writing, and about that monstrously difficult thing, structure. In this section Dani shares a line from Aristotle that I have heard her say in person more than once: “Action is not plot, but merely the result of pathos.” She declares that “if you have people, you will have pathos” and goes on to say that for artists there is “no satisfaction whatever at any time. There is only a queer, divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than the others.” The blessed unrest of which Dani speaks gives me that now-familiar sensation (because I’ve felt it many times when reading her work) of being known from the inside out, of someone reading my mind and putting into words something I’ve felt but been unable to articulate. Yes. The pathos that we see, she is saying, is unavoidable, and though it hurts, we must keep seeing it and sharing it.

Middles is my favorite part of Still Writing. Dani urges us not to give up, to believe that “just at the height of hopelessness, frustration, and despair… we find the most hidden and valuable gifts of the process.” I am in the middle myself – of writing, of thinking, of life itself – and her words encourage me more than I can articulate. “It has been said that the blessing is next to the wound,” Dani writes in Middles, and I began to cry. There’s no question this is true of me: my wound and my wonder are two sides of the same truth, of the frank astonishment at this world that is the lens through which I see every day. Again Dani describes something so true it sends a shiver up my spine:

I’ve learned that it isn’t so easy to witness what is actually happening. The eggs, the cows. But my days are made up of these moments. If I dismiss the ordinary – waiting fort the special, the extreme, the extraordinary to happen – I may just miss my life…. It is the job of the writer to say, look at that. To point. To shine a light. But it isn’t that which is already bright and beckoning that needs our attention. We develop our sensitivity – to use John Berger’s phrase, our “ways of seeing” – in order to bear witness to what is. Our tender hopes and dreams, our joy, frailty, grief, fear, longing, desire – every human being is a landscape….This human catastrophe, this accumulation of ordinary blessings, of unbearable losses.

Endings are about the “prickly, overly sensitive, socially awkward group of people” that form a writer’s tribe (just that description alone makes me sigh with identification), the themes that “sharpen and raise themselves as if written in Braille,” the necessity of telling our stories, even when it is hard, the fearful uncertainty of the business side of a career in writing, and the dangerous, seductive power of envy. It is also in Endings that Dani reflects on some of the grand themes of the writing life. It is in this section that we see most clearly that Still Writing is about more than writing: it is about living in this world, about paying attention, about honoring where we came from while recognizing where we are, about those we love and can trust and those whose intentions are less clear. It is about remaining open to the world, even – or maybe most especially – when it causes us pain.

Too often, our capacity for awe is buried beneath layers of perfectly reasonable excuses. We feel we must protect ourselves – from hurt, disappointment, insult, loss, grief – like warriors girding for battle. A Sabbath prayer that I have carried with me for more than half my life begins like this: “Days pass and the years vanish, and we walk sightless among the miracles.

We cannot afford to walk sightless among miracles. Nor can we protect ourselves from suffering. We do work that thrusts us into the pulsing heart of this world, whether or not we’re in the mood, whether or not it’s difficult or painful or we’d prefer to avert our eyes. When I think of the wisest people I know, they share one defining trait: curiosity. They turn away from the minutiae of their lives – and focus on the world around them. They are motivated by a desire to explore the unfamiliar. They are drawn towards what they don’t understand. They enjoy surprise. Some of these people are seventy, eighty, close to ninety years old, but they remind me of my son and his friend on the day I sprung them from camp. Courting astonishment. Seeking breathless wonder.

Still Writing is a book to read carefully and to savor over and over. I’ve read it twice myself already, and I know it will join books like Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life in the pantheon of those volumes I trust most and revisit most often. I’m fortunate and grateful to know Dani and feel sure that this volume, which contains so much of her wisdom, her heart, and her soul, will inspire passionate devotion in many, many readers.